Bike Racks, Bikeability, Infrastructure, Liveability, Walkability, Schools

Walkability

Bikeability, Liveability, Walkability, Infrastructure

Bikes over Bridgetown Part 2

The most important bike route improvements currently happening in Portland,

part 2

We recently published part one of this post—you can read that here. Today we’re highlighting one more of our favorite new infrastructure developments currently underway in Portland, and closing out this two-part discussion with an international example of carless infrastructure that combines ingenuity, sustainability, functionality and environmental considerations to really shift the thinking on the relationship between roads, ped/bike paths, and the natural world.

Gideon Overcrossing

WHAT IT IS

This bike and pedestrian crossing is being constructed over the MAX Orange line and Union Pacific Railroad tracks, connecting SE 14th Avenue and SE 13th Place at Gideon Street.

WHY WE’RE EXCITED ABOUT IT

This is notoriously one of the worst places in Portland to get stuck at a crossing, with freight trains sometimes resting at a full stop across the intersection for up to two hours. While this bridge can’t help those poor souls in cars, it will be equipped with stairs and elevators on both sides to ferry cyclists and pedestrians safely across. A former crossing had to be removed during the construction of the Orange Line, and this return has been a long time coming. Currently your best bet for getting across the tracks is at SE Milwaukie Ave., where it splits into 11th and 12th. But, again, stopped trains are an issue. Cyclists are often seen climbing over the couplings of active freight cars—what? People. Let’s please stop doing this. Delays are such a pain point to commuters and businesses alike that a development group in a nearby building built a uni-functional website specifically to track whether or not a train is blocking the intersection. At press time, isatrainblocking11th.com reported: “NO.”

WHY IT’S IMPORTANT

This crossing will unite the busy greenways of Gideon Street and Clinton Street, and give cyclists an alternative to climbing between railcars (again, let’s don’t) or waiting endlessly for the intersection to be clear. It will also effectively finish off the Clinton to the River project, a mostly-complete 2.8-mile bicycle route that’s been in the works for nearly a decade. Another example of Portland’s ongoing commitment to reshaping how the city handles vehicles, bicycles, and the relationship between the two.

Bonus! The Blauwe Loper Bridge

While Portland keeps finding new ways to route bike and pedestrian traffic across bodies of water, through wildlife preserves, and over busy roadways, the Netherlands recently began construction on a bridge that will span all three, and more. There’s so much to love about this project we’re not sure where to start.

The Blauwe Loper—or “Blue Carpet”—will be the longest bike/ped bridge in Europe and one of the longest in the world. At completion of phase one it will span 800 meters, with plans to ultimately extend it to more than a kilometer. (Technically, China’s Bicycle Skyway holds the title, knifing through the congested core of Xiamen and clocking an impressive 7.6 km—almost 5 miles—of continuous dedicated bike lanes. It’s arguably more of an elevated bicycle highway than a true bridge, but who are we to argue.)

This news should come as no surprise; in the Netherlands, bicycling is a universally-enjoyed pastime and primary form of transportation. It’s often reported that there are more bicycles than people in the Netherlands, and over 32,000 km (about 20,000 miles) of dedicated bike path crisscross the region’s mostly-flat terrain, making it the perfect setting for a bike-first culture.

Just wait, it gets better.

Tantamount to pedestrians and bicyclists, one of the top design considerations for the bridge was a much longer-tenured inhabitant of the region: bats. The Blauwe Loper will be painted a “bat-friendly” green and outfitted with solar-powered LEDs, as an aid for bat colonies to avoid the bridge and navigate from their habitat in a nearby park to the feeding grounds at Oldambtmeer lake and back home again.

Lastly, builders of the Blauwe Loper claim that the structure, built mostly of resilient Central African hardwood sourced in Gabon, will last at least 80 years. As project leader Reinder Lanting told a local daily newspaper, “This bridge is not going to rot. That is because it is technically well designed. The wood is not pressed together but has a sort of venting system.”

We love the ingenuity and radical thinking at work here. You can learn more about the project at Blauwestad.com.

As we said in part one of this post, follow the progress of these projects online, go check them out in person, and use them when they’re completed. Take advantage of pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure to get out and enjoy Portland, or Blauwestad, or wherever you’re reading this from. We’ll see you out there.

Bikeability, Liveability, Walkability, Infrastructure

Bikes over Bridgetown

The most important bike route improvements currently happening in Portland,

part 1

The City of Portland is constantly working to improve traffic flows, making it easier for all of us to get where we’re going. You can spot efforts across the city marked by bright-green painted lanes and cute little bicycle-shaped traffic signals that remind us of novelty pasta. But the net effect is much larger than these individual efforts. Each new bicycle lane and neighborhood greenway represents the effort to reduce carbon emissions and encourage active forms of transportation. We think that’s worth celebrating. In this two-part post, we’re highlighting some of our favorite projects currently in the works: three new carless bridges in Portland (plus a bonus bridge in the Netherlands!) that represent an easier way to get across town on two wheels, and much more.

Congressman Earl Blumenauer Bridge

WHAT IT IS

Also known as Sullivan Crossing, the bridge’s official name honors the bowtie-sporting bicycle-championing civil servant who’s been lobbying for its existence for decades. The bridge will span Interstate 84 at NE Seventh Avenue, connecting the Lloyd and Central Eastside Industrial districts.

WHY WE’RE EXCITED ABOUT IT

The Blumenauer Bridge is part of Portland’s Green Loop initiative, an ambitious plan to create six miles of connected park space through the heart of the city. The Green Loop is designed to provide access to local businesses and services by foot, bike or mobility device (like e-scooters). The Green Loop is a tangible symbol of Portland's commitment to improving access to parks, nature, and alternative transportation, and this bridge will be a linchpin of that effort. You can check out an earlier post we published on the Green Loop here.

WHY IT’S IMPORTANT

Anyone who walks or bikes in the area knows how desperately this solution is needed. Currently, your best route over the interstate is the NE 12th overpass, a heavily-trafficked stretch of pocked pavement. Other options are the MLK and Grand Avenue connections that make up 99E—literally a highway. Less than ideal.

With plenty of bike lanes and neighborhood greenways weaving their way through the inner-eastside, this bridge feels like the missing link and a welcomed addition to the area. Ground has been broken and construction is slated for completion in the spring of 2021. The bridge will be 24 feet wide to accommodate emergency response vehicles if necessary. It will feature a 10-foot pedestrian path, a 14-foot two-way bicycle track and, according to Commissioner Chloe Eudaly, “come hell or high water, somewhere on this bridge, there will be a bow tie.” We love that.

Flanders Crossing

WHAT IT IS

In an equally crucial move, this new bike and pedestrian bridge will span Interstate 405 at NW Flanders Street, linking Nob Hill and the Alphabet District to the Pearl.

WHY WE’RE EXCITED ABOUT IT

Not only does this project consist of a carless bridge over the 405, it’s become part of a larger effort known as the Flanders Bikeway. In total, the Bikeway is planned to transform NW Flanders Street from 24th all the way to Naito Parkway, including the Crossing. Bike and pedestrian traffic will be prioritized while vehicle flow is limited to discourage cut-through traffic. The project has loomed on the City of Portland’s radar for years, stuck in priority purgatory, but construction is finally slated to begin this year. If it’s done well, this project can act as a blueprint and a catalyst for Portland to prioritize alternative modes of transportation across the city.

WHY IT’S IMPORTANT

Currently the best way to cross the 405 by bike in that area is Everett Street (heading east) and Glisan (going west). The two overpasses make up the heart of a busy freeway ramp network, and even with improvements over the last few years, neither offers much in the way of bike or ped facilities. With initiatives like Better Naito Forever and the previously-mentioned Green Loop also in the works, the bridge and bikeway can connect retail, dining and professional offices in Northwest to the Waterfront and the rest of the city.

Track the progress of these projects online, go see them in person, and make use of them when they’re completed. We certainly plan to.

In the meantime, keep an eye out for part two of this post, which will cover another important Portland project plus some bonus international bike news!

A Brief Aside

We’re in the middle of a global pandemic. There’s plenty of discussion happening on the subject and we don’t feel like it’s our place to weigh in. We want to applaud healthcare professionals and essential workers, and thank everyone for doing their part to help us all get through this.

Bike Racks, Bikeability, Liveability, Walkability

Bike parking, plus one, plus one…

We’re proud to announce 86 of our stainless steel Arc bike racks are part of the Nicollet Mall revitalization in Minneapolis, Minnesota. We’re doubly proud to add that the Minneapolis Downtown Improvement District have continued to install a few more Arc’s every month or so since 2016.

David Sokol of Architectural Record writes:

“Today, this downtown zone is being revitalized as a mixed-use neighborhood, and Minneapolis is again reshaping its urban fabric by implementing a redesign of the Nicollet Mall, led by the landscape architecture and urban-design firm James Corner Field Operations, with lighting by New York–based Tillotson Design Associates (TDA) and local expertise contributed by the notable Snow Kreilich Architects and landscape architect Coen+Partners.”

Read more and see images of our Arc racks here:

https://www.architecturalrecord.com/articles/14200-nicollet-mall-in-minneapolis

Bike Rooms, Bikeability, Custom Work, Liveability, Walkability

Bike Garages: Where to Park Your Bike, When Everyone Rides Their Bike

Welcome to Amsterdam!

If you read our blog, then you might already know that Amsterdam has some of the world’s best-designed bike infrastructure, which helps explain why over half of all commutes in the Dutch city are by bike. This has lots of benefits—less traffic congestion, better health, safer streets—but it also poses a surprising problem: where to put all those bikes when people aren’t riding them.

In residential neighborhoods, the solution is bike racks and corrals, often mounted on sidewalk bump-outs in quiet side streets.

But what about places where everybody wants to park? When Amsterdammers take the train, go to the library, work in a big office park, or see a movie or concert, they often arrive by bike. At places this popular, a few racks won’t cut it.

Enter the underground bike garage. Most Dutch cities have a few of them; Amsterdam has over 20. To American ears, it might sound extreme to dig out a garage just for bikes, but it’s not really that different from the bike rooms that office and apartment buildings in the US increasingly offer. In both cases, the idea is simple: provide a safe, easily accessible, weather-protected place to park, and people are more likely to make biking a habit, and not take up so much expensive car parking. In the Netherlands, the logic (and benefits) are just scaled up to the city level.

Here’s one example of a gemeentelijke fietsenstallingen (municipal bike parking) garage. This one’s next to Paradiso, a legendary concert hall and nightclub located in a converted church next to the Singelgracht canal.

A lot of thought goes into the design of garages like these, starting with getting in and out. Larger garages often have ramps or moving walkways, but this is a relatively small fietsenstallingen, so you take the stairs. Notice, though, that there are small channels on either side to roll your bike down.

On closer inspection, these turn out to be more than just ramps. The “downhill” channel on the right side is lined with stiff bristles that grip your bike tire and slow its decent. The “uphill” one is actually a tiny conveyor belt! — simply roll your bike onto the yellow strip, lock your brakes, and it automatically starts moving, carrying your bike up the steps while you walk alongside.

Because space is at a premium, nearly all garages use double-decker parking, with an elevated row of racks that slide out and tilt down on a small pneumatic piston. This allows for incredible density: Amsterdam’s newest bike garage in the Strawinskylaan office district holds 3750 bikes, but fits underneath a road overpass.

Most garages are staffed and guarded, and charge a (very small) fee for secure, overnight parking, which you pay with a debit or transit card upon check-out. The larger ones also offer bike repair stands, in case you need to make an adjustment or fix a flat before heading out.

And some of them are quite beautiful.

Interested in adding a little Dutch-style convenience to your office, residential, or municipal development? Our range of racks and furniture is extensive, and we customize for just about any situation.

Bike Racks, Bike Sharing, Custom Work, Walkability, Bikeability, Liveability

Sustainability That Looks as Good as It Feels

Portland State University just celebrated the grand opening of the Karl Miller Center, a state-of-the art facility featuring a bright, open atrium. This eye-catching building is a campus jewel, so the bike racks slated for installation right outside need to look the part.

Clint Culpepper, the Bicycle Program Coordinator at PSU, could have purchased brand new racks to install, but utilizing refurbished bike racks better aligns with the university’s focus on sustainability. “Nothing would make me feel worse than turning a bunch of bike racks that were totally usable and serviceable into metal recycling just to buy brand new ones,” he said. Last year Clint enlisted the services of Huntco Site Furnishings to transform dozens of old, beat up staple racks into freshly painted bike corrals, and he decided it was time to refurbish a second batch.

From Clint’s perspective, the hardest part of the process is ensuring there is adequate capacity for bike parking while the old racks are removed and refreshed. The rest is as easy as making a phone call. Huntco picks up piles of assorted staple racks, sorts them, and welds matching racks onto sets of rails to make bike corrals. Fresh powder coating is applied and then the corrals are delivered back to PSU, looking good as new and ready for installation.

The updated bike corrals don’t just benefit campus cyclists. “Everyone on campus likes it when the bike racks look nice,” Clint reports. Not every user of a building wants to have a bike rack sitting right outside the front door, but there’s less resistance when the racks look good. So when the next batch of refurbished racks is delivered in a few weeks, rest assured that the Karl Miller Center will get the dazzling accessories it deserves.

All Photos: Thomas Teal

Bike Racks, Bikeability, Liveability, Walkability

More Ideas from France: How to Turn an Orphaned Lot into a Neighborhood Treasure

Every city has orphaned lots: those islands of land stranded by an unfortunate intersection, too small or oddly-shaped to build on. But while some linger as undignified patches of asphalt or concrete, others become true neighborhood amenities, often because of smart use of street furniture and bike infrastructure.

Here in the US where uniform grids reign supreme, a triangular plot of land is pretty rare. But in European cities, defined by centuries of overlapping urban design, they’re everywhere. Lille, a city in northern France that we’ve written about before, is no exception. Here’s one cut-off triangle, in the working-class Moulins neighborhood:

What potential do you see in that little triangle? A park? A bikeshare station? A patch of calm in the urban fabric that draws people together? How about all three?

Here’s what it looks like at ground level:

This little scrap of land, it turns out, has a lot going on: shaded benches, a line of bike racks, a heavily-used bikeshare station, and a perimeter of bollards to protect the whole thing. What could’ve been an urban afterthought is, instead, a neighborhood gathering point, serving commuters in the morning and evening, and friends and families in the afternoon and evening.

It also makes nearby outdoor seating much more attractive—here’s a mid-morning view from “Le Triporteur”, a restaurant/cafe across the street:

By 7pm, that patch of sidewalk will be packed with local residents, eating frites and drinking Belgian beer, despite heavy traffic on the major avenue right out front.

It’s a scene replicated all over town, and in countless other European cities: find an orphaned bit of land, protect it from traffic, add features that invite bikers and pedestrians, and you quickly have a little slice of community, that entices people outside and into local businesses.

Here’s another example, along Rue Solferino, a busy street about a mile away:

What was just a strip too narrow to build on instead becomes a lovely, bollard-protected public square, enhanced by trees, art, and seating for a facing cafe

Obviously, there’s more to these wonderful public spaces than just some bollards and a couple of benches, but they couldn’t exist without them. Infrastructure does more than just provide a place to sit. It also defines a space and lays a foundation. And what these tiny parks—and thousands of others like them—clearly show, is that once that foundation is laid, amazing things can happen in the most neglected places.

Bikeability, Liveability, Walkability

Plan for Pedestrian and Bicycle Green Loop Unveiled at Design Week Portland

Image: Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability

According to the 2035 Comprehensive Plan published last year, the city of Portland is expected to grow by 260,000 people in the next two decades. As any Portland resident will tell you, the current infrastructure does not support the transportation needs of today’s population, let alone this anticipated spike. To accommodate such rapid growth, the Comprehensive Plan advocates for solutions that will make Portland a more walkable, bikeable, transit-friendly city, by both increasing access to active transportation and rethinking how neighborhoods are developed.

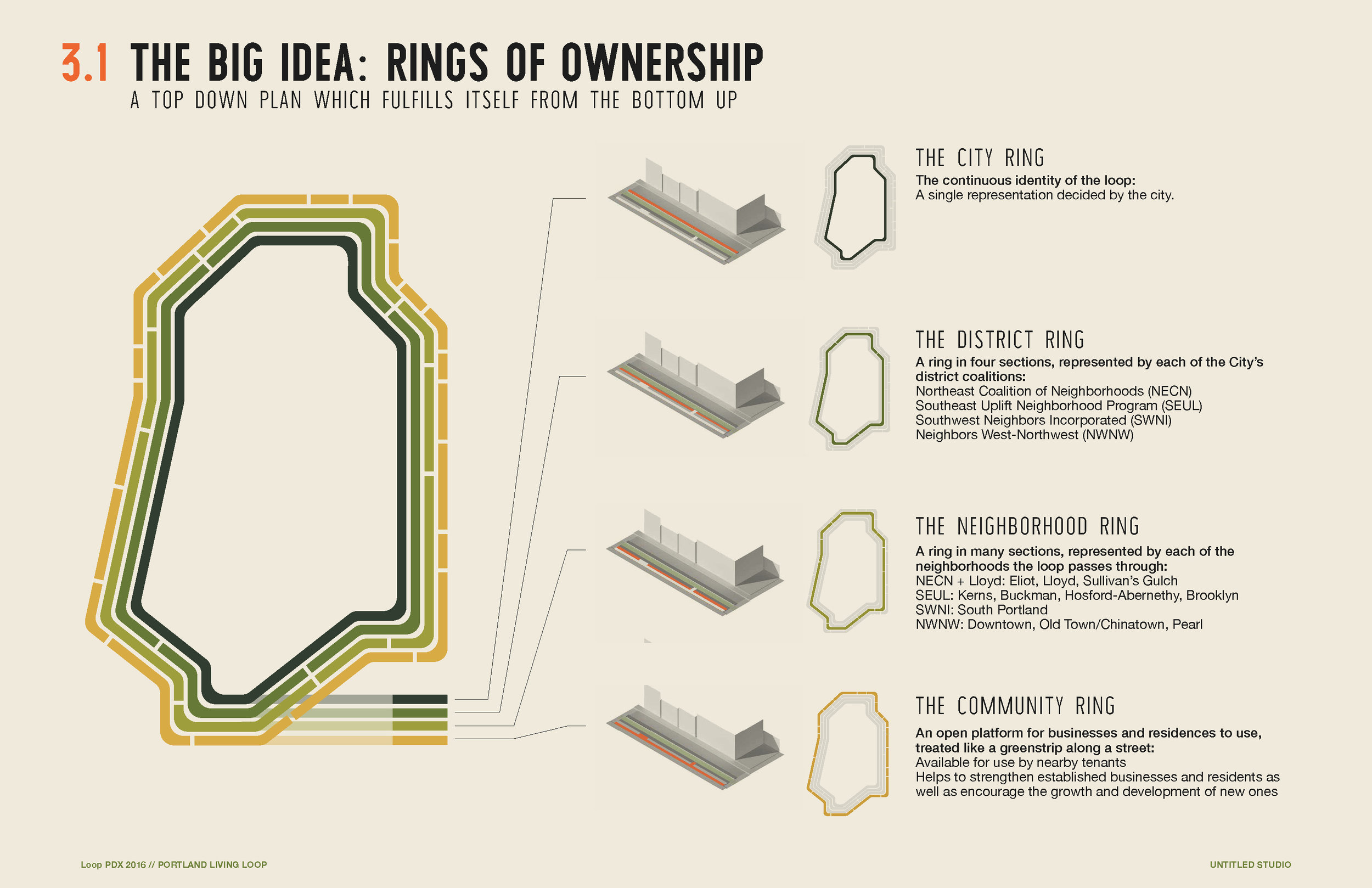

One of the proposed projects is construction of a six-mile pedestrian and bicycle “green loop” that will connect the inner east and west sides of Portland. The John Yeon Center for Architecture and the Landscape partnered with Design Week Portland to solicit creative proposals to conceptualize and design the loop. The winner of the competition, Untitled Studio, not only imagined an ecofriendly, multi-use transportation path but also introduced a collaborative process as the means to design it.

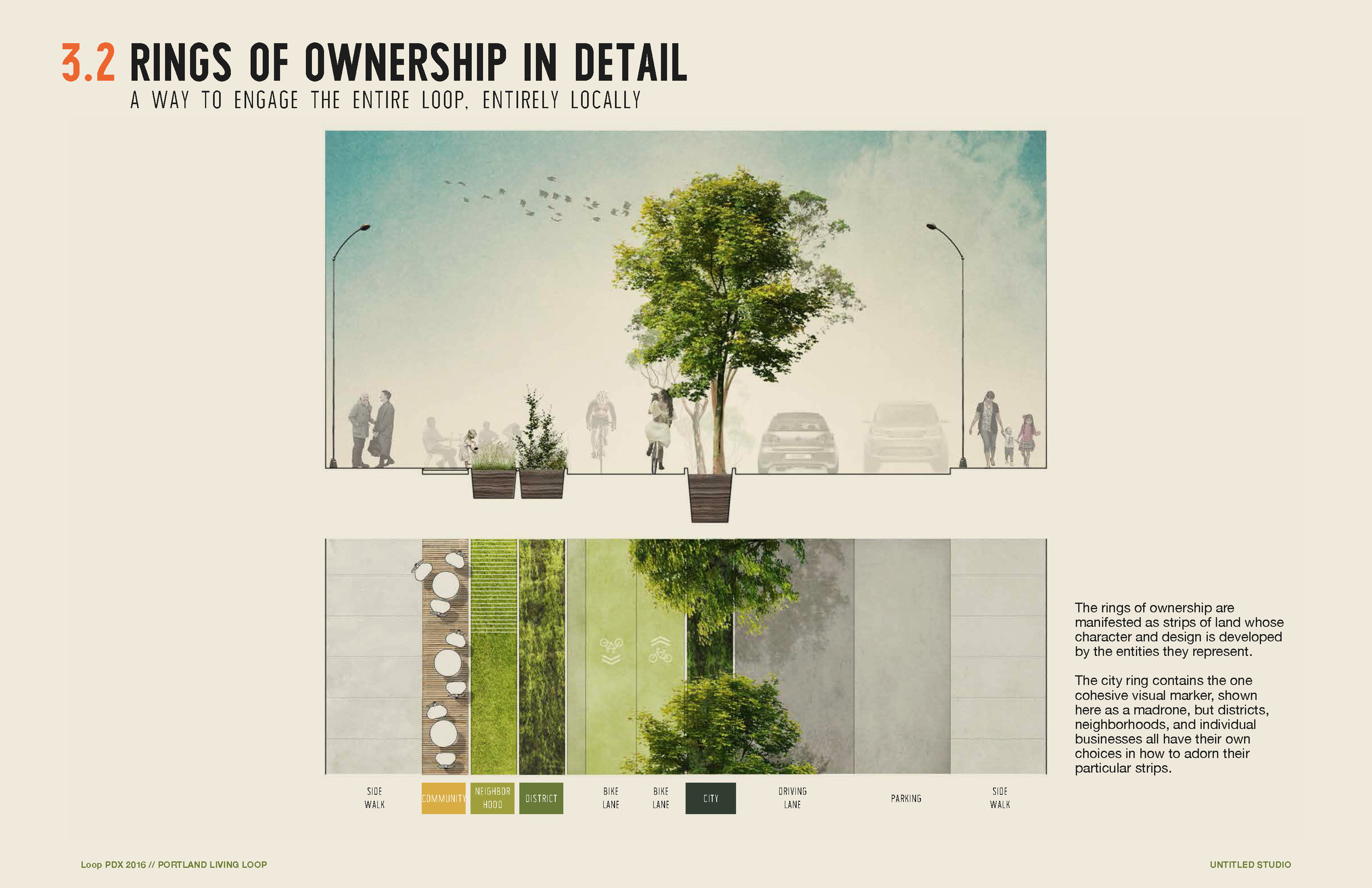

Last month at Design Week Portland Headquarters, Untitled Studio revealed their vision for “Portland’s Living Loop.” The exhibit generated excitement for the project and included opportunities for audience engagement, mirroring the participatory process that will inform the green loop’s development in the years ahead. Though the loop will serve as a critical pedestrian and bicycle route across the city, Untitled Studio also positioned it as a destination and center of community. According to their model, the loop is divided into four lanes, corresponding to the Central City, District, Neighborhood, and Block. The purpose and design of each lane is decided by the people represented by the lane, from the city as a whole down to the individuals, families and businesses that reside along a particular block.

Image: Untitled Studios

Images from Untitled Studio's green loop proposal, view the full proposal here.

The possibilities for what the green loop could become are endless. Could the neighborhood benefit from an outdoor fitness space with fixtures installed for exercise? Would an urban garden plot be advantageous for a particular block or do businesses need space to install dedicated bike parking? Does the district want a central space for the community to gather, with ample benches for seating and trees for shade on hot summer days? According to the model, any of these options–and so many more–could be incorporated into the loop alongside the transportation paths.

Image from Untitled Studio's green loop proposal, view the full proposal here.

Civic projects of this scale are often dictated by the local government. Untitled Studio proposed this four-lane model as a way to engage the residents of Portland and ensure that the people who are most affected by construction of the loop are entitled to contribute to its design. Neighborhoods might hold town hall meetings or survey residents to identify solutions that best serve their community. Individuals and businesses on a single block might organize a potluck to meet each other and brainstorm ideas for their lane of the loop.

Image: Design Week Portland, community feedback wall, via Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability

How this participatory model of design will translate from vision to reality is uncertain. Construction of the green loop will take place in stages as funding is secured, with a few key portions already completed (Tilikum Crossing) or in development. Yet if this process is successfully implemented, it could become a model for numerous other pedestrian and bicycle greenway projects that are slated for development in the 2035 Comprehensive Plan.

View the green loop presentation here.

Liveability, Bike Sharing, Walkability

What’s French for Bollard?

We’re in France this week! Well, one of our team is anyway, spending some time with family in the friendly northern college town of Lille.

This being Huntco, what we’ve noticed about Lille, even more than the beautiful old cobblestone streets or the legendary beer (it’s only 30km from Belgium) is the bollards. Like a lot of mid-sized French cities, Lille is a great place to walk and bike, with a wonderfully rich street life — and one of the reasons why is extensive and thoughtful use of bollards, in ways that might be surprising to folks in North America.

The Place du Général de Gaulle is a good example. Usually just called the Grand Place (“big plaza”) by locals, this is a broad, brick-paved square fronted by bookstores, cafes, shops and a historic theater. It’s the undisputed heart of the city, frequented by thousands of people a day who come there to meet, shop, drink or just hang out. It also has a street snaking right through the middle of it, and a 422-space parking garage underneath.

So how do open up a big, public space to cars without turning your beloved Place into a parking lot? In Lille, you do it with bollards.

Using dozens of slender, elegant bollards at about 8 foot intervals, the city has demarcated a “street” that directs traffic through the plaza, while making it clear that cars are sharing the space with (far more numerous) people walking and biking. For pedestrians, the bollards just barely interfere with the flow of foot traffic, indicating where to watch out for vehicles but keeping the space permeable.

For drivers, the message is clear: proceed to the underground parking lot, or keep moving, slowly, until you’re clear of the shared space.

Just north of the Grand Place is another smart use of bollards along Rue Faidherbe, a short, majestic boulevard connecting the plaza to the city’s busiest train station.

In this case, the bollards line the one-way street (with two-way bike lanes), protecting broad sidewalks full of shoppers while making it easy to cross at any point. Strategic gaps in the bollards define intersections with side streets, funneling cars in a predictable way without impeding walkers — and leaving plenty of room for the city’s cafe culture to thrive.

Like the bollards that Huntco manufactures, these are unobtrusive enough that they become part of the urban fabric, not an interruption to it — in fact, they might even be a bit beloved.

The city also uses different types of bollards to lend a sense of place to different areas. Here’s a different type of bollard as you head toward the are de Lille Europe — the newer train station where the Eurostar from London stops.

You’d be hard pressed to find a city anywhere in the US that uses bollards so prolifically, or applies them so expressly toward directing cars, rather than just protecting pedestrian spaces. It’s a refreshing approach that could have some real impact in cities here, especially ones hoping to spur the kind of placemaking that’s clearly so good for business in cities like Lille.

Oh, and in case you’re wondering, the word bollard is French! And if Lille is any indication, France may well be the bollard’s homeland.

—

Story and photos by Huntco team member and world traveler Carl Alviani.